2023 NWSA/AAAS-PD Conference

Aphrodite: Security Properties of RISC-V

Abstract

Hardware specification mining is a relatively new line of research that aims to develop a set of validation properties for use during the design validation phase of the hardware life-cycle. Prior work in this field has targeted open-source RISC architectures and relies on access to the register transfer level design including developers’ repositories, bugtracker databases, and email archives. We develop Aphrodite, a tool for specification mining generalized at the instruction set architecture (ISA) level. We use a full-system emulator with a lightweight extension to generate trace data over arbitrary assembly code or existing suites, such as Linux boot, and generate hardware properties which include both functional and security properties. Using the motivating example of the established GPR0 security property (for “General Purpose Register 0”, it is the property that the zeroth general purpose register must always be set to 0 for correct calculation of security-relevant operations), we show that Aphrodite may extract security-relevant, as well as functional, properties of the design. Our analysis provides insight into those properties that are guaranteed by the ISA and those that are required of the operating system.

Summary

I spoke yesterday afternoon at the joint annual meeting of the Northwest Scientific Association and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Pacific Division at Western Washington University in Bellingham, WA. The image above is a link to my slide deck from that presentation, where I go through why we should care about hardware security, what it means for hardware to be secure, and how we use Aphrodite to study security properties. While it wasn’t necessarily a conference for computer scientists (indeed, a majority of presenters were from the Earth sciences), I did get a lot out of the experience, and I had the opportunity to visit a beautiful college campus while doing it.

My research notes give a blow-by-blow account of how I developed the software, as well as my learning process throughout the summer, as I gained a more detailed understanding of instruction sets, hardware design, processor architecture, and (perhaps most importantly) how to use open-source tools for software development.

The presentation gave a much higher-level and better organized overview of my research process. The summary below is from my Powerpoint speaker notes.

Overview

Our guiding question for this research is, “What are security-relevant properties of computer hardware?”

To answer that question, we have to collect data, analyze that data, and report the results.

We want to analyze what data the processor is holding, and where it’s holding those values. The key here is that we don’t want to change any of those values, so we have to “look in” from the outside without using the hardware to tell us what values it contains. It would be hard to do this on an actual physical computer chip, so we want to model our processor in software. As a result, we can print those values from internal data structures to the “host” machine without changing them.

The next step is data analysis. We use a technique called “data mining” to find out what the processor’s properties are. Then, we can check them against common security weaknesses, which have been studied and enumerated for a long time by people far smarter than me.

Finally, we have found security properties that we can now report! That’s this talk!

We use QEMU to virtualize the processor. It is a well-documented, open source tool, which makes it ideal for academic research—no pesky licensing fees or use restrictions. Next, we need a program that performs security-related tasks, such as an operating system. We chose Fedora Linux, a lightweight, open source OS. The tool we used for data mining is the Daikon invariant detector, a machine learning system developed by our colleagues at the University of Washington.

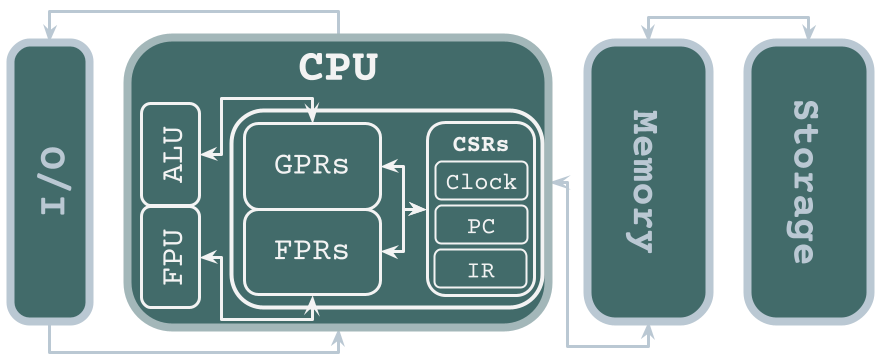

So, what is this thing we’re studying, the computer processor, and what does it do?

The Central Processing Unit (CPU) can be considered the “control center” of a computer, because it’s where operations are performed. It’s organized into registers and logic units. There are different types of registers: CSRs, or Control and Status Registers, do a lot of important functions, many of which are security-relevant. Shown here are a few of many. The instruction register keeps track of the current instruction, the program counter gives us the address of the next instruction, and the clock keeps everything moving with electric pulses every nanosecond or so. Hardware manufacturers like to brag about the number of clock pulses per second, typically a number in GHz. General-purpose registers store data such as memory addresses, integers, characters, and more. These values interact with the Arithmetic Logic Unit, which has all the circuitry to perform operations such as addition, multiplication, bit shifts, AND, OR, XOR, NAND, NOT, XNOR…. The final category of registers I studied are the floating-point registers, which store fractional and very large values, kinda like scientific notation for binary. The Floating-Point Unit handles their specially-formatted computations.

There are two main approaches model a processor in software: simulation and emulation.

Simulation models the actual interactions of different processor components and the wires that connect them. At this level, we don’t have a high-level abstraction of “instructions,” what we have are bits in the instruction register that open and close different circuits within the CPU, for instance, the adding circuit within the ALU or the multiplication circuit in the FPU.

Emulation models what we call the instruction set architecture of the processor, which does have our abstract notion of an instruction. However, emulation doesn’t capture all the quirks that come with the actual hardware implementation of an ISA. I chose emulation for this project because the tools were readily available and relatively easy to install and configure.

There are other hardware security weaknesses we can’t detect at this level, namely information side channels, e.g. power usage or heat production, that an attacker could exploit. What we can detect at this level, however, is violations of implicit or explicit security agreements made between software and hardware, such as accidentally storing a private key in an unprivileged location such as a GPR.

Instructions are the human-readable abstraction of the actual bits that open and close different circuits in the CPU. Instructions can invoke arithmetic operations, load values from memory, send data to memory, control I/O, and other tasks. High-level code like Python is parsed and interpreted into instructions.

Here are two examples of RISC-V instruction formats.

The low-order bits of the instruction tell us what operation to perform (opcode), the “destination register” specifies where to send the result (rd), the function bits tell us what type of a load/store/add operation we’re doing (funct*), and the remaining bits have the actual operands, either as source registers (rs*) or encoded directly in the instruction itself as immediates (imm[*]).

Instructions are organized into an instruction-set architecture.

An ISA allows executable programs to be portable across different types of processors, for instance from different manufacturers, or different generations from the same manufacturer. It’s one of the last steps in translation from software to hardware, what we’re primarily studying in this project.

There are two main approaches to instruction-set architecture: reduced (RISC) and complex instruction set computers (CISC).

In a RISC architecture, a single operation corresponds to a single instruction. We have to LOAD, operate, and only then can we STORE back into memory. This makes it difficult to program directly in assembly for a RISC processor (although not impossible, as we’ll see later).

CISC architectures, on the other hand, can invoke, for instance, a load, a multiply, and a store, all with a single instruction. This means one program uses fewer instructions, and therefore fewer main memory accesses. This is advantageous from an electrical engineering perspective, which is why Intel uses this approach.

If Intel uses a CISC architecture, why would we study RISC-V? Well, x86, the Intel ISA, is a tightly guarded trade secret, and RISC architectures are easier to study in an academic setting. A single RISC instruction is more predictable and executes in a fixed amount of time. Additionally, RISC-V is open source, and funded in part by hardware manufacturers, partially so that we academics will do our magic and give them useful information about the characteristics of hardware.

RISC-V

The RISC-V specification is a hundreds of pages long PDF that has all the information to implement a processor in wires and silicon. It specifies properties that we will verify in our research, for instance, that the x0 register is always equal to zero, our motivating example in this talk. We can do even more detailed analysis of small programs based on the spec.

If any of the standards in the spec aren’t observed in practice, that might have security implications—they’re the implicit and explicit security agreements we’re looking for.

.global _start # Initialize the program at “_start” label

_start:

lui t0, 0x10000 # Load address of serial port into register t0

andi t1, t1, 0 # Zero out t1

addi t1, t1, 72 # Add (int)‘H’ = 72 to t1

sw t1, 0(t0) # Send value of t1 == ‘H’ to location addressed by t0 (UART0)

# The previous three lines are repeated for

[...] # ‘e’,‘l’,’l’,’o’ and finally

# LF (line feed, aka ‘\n’)

finish:

beq t1, t1, finish # Jump to label finish if t1==t1

The above program is written in RISC-V assembly and prints the string "Hello" to the UART0 serial port (which corresponds loosely to the high-level stdout). Each character is represented by its ASCII numerical value, since hardware doesn’t know what a character literal is, much less an entire string. The program ends with an infinite loop to prevent it from accessing memory locations it shouldn’t. Hardware doesn’t automatically know when to stop executing a program (like in high-level languages), so if you aren’t careful, your program might start reading memory locations that aren’t actually instructions—called a “memory leak.” That, of course, is a security weakness in software rather than in hardware, therefore not directly related to our research, but still useful to note.

Aphrodite

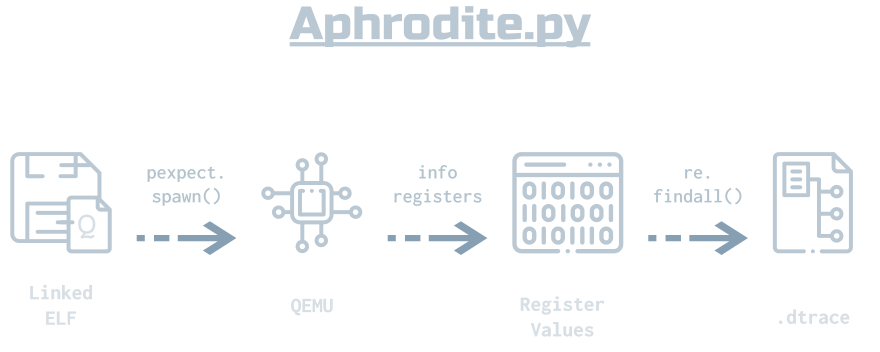

We feed an executable into Aphrodite, a Python script that runs QEMU and uses QEMU runtime tools to retrieve register values and write them in a format Daikon understands.

At this point in the process, I had two different types of traces to work with: the output directly from native QEMU tools on the left, and the Daikon input format on the right. Notice the irrelevant data on the left, and that the qtrace register values are fixed-width hexadecimal fields, but Daikon works in decimal.

i\x1b[K\x1b[Din\x1b[K\[...] ..tick():::ENTER

pc 0000000000001000\r this_invocation_nonce

mhartid 0000000000000000\r 1

[...] pc

x0/zero 0000000000000000 4096

x1/ra 0000000000000000 1

x2/sp 0000000000000000 mhartid

x3/gp 0000000000000000\r 0

[...] 1

f28/ft8 0000000000000000 [...]

f29/ft9 0000000000000000 f31/ft11

f30/ft10 0000000000000000 0

f31/ft11 0000000000000000\r 1

[...] [...]

Here’s some pseudocode describing Aphrodite’s behavior. We take the string output from QEMU and parse it for register name/value pairs, at this stage in a single string containing both label and value. Next, we make sure that we actually had novel register values in the output, since sometimes the script runs faster than QEMU can update, and sometimes the output will just be noise, so this check avoids unspecified behavior. Next, we further split the label/value strings into String label and Integer values. Do this until it times out, based on a constant near the top of aphrodite.py.

- Create a .dtrace file and give it a unique name based on current system time

- Spawn QEMU with initial parameters

- While not timed out:

- Parse

info registersoutput for register values, adding to listvals - If

valsis not equal to the last timepoint and is nonempty:- Split

valsentries into tuples:(label, value) - Cast the

valuehex string to an integer - Write these label/value pairs to .dtrace in the appropriate format

- Split

- Send next

info registerscommand to QEMU

- Parse

- Quit QEMU and close .dtrace

Here’s a snippet of the actual Python code that parses register values and writes them to the trace file. As you can see, this uses a fairly complex regular expression, since it is looking for substrings of a very particular format in the qtrace output.

The FOR loop on the bottom juggles our name/value Strings into name/value pairs, does the necessary conversions, then writes it in the Daikon-approved input format.

# find all register name/value pairs on current line

# returns empty list if no register values found,

# i.e. the output was not a string of register/value pairs

vals = re.findall(r"[a-z0-9/]+\s+[0-9a-f]{16}|\w+\s+[0-9a-f]x[0-9a-f]",out)

[...]

# Parse register/value pairs into lists

for reg in vals:

reg_val = re.split("\s+",reg)

# hex string to int: `int("ff",16)` -> 255

reg_val[1] = int(reg_val[1],16)

# register name\n value \n constant 1

dt.write(reg_val[0]+"\n"+str(reg_val[1])+"\n1\n")

# for copying these values into the tick exit

tpoint.append(reg_val)

Now we have our trace, and the .decls file that tells Daikon what it’s looking for, constructed separately. These are both the pieces we need to run Daikon and look at actual observed properties of the RISC-V architecture.

f21/fs5 == f26/fs10

pc != 0

mhartid == 0

mip >= 0

mideleg one of { 0, 546 }

medeleg one of { 0, 45321 }

mtvec one of { 0, 2147484904L }

x0/zero == 0

f0/ft0 >= 0

[...]

f16/fa6 >= 0

f19/fs3 one of { 0, 4607182418800017408L }

f20/fs4 one of { -4616189618054758400L, 0 }

f21/fs5 one of { 0, 4472406533629990549L }

f22/fs6 >= 0

f23/fs7 >= 0

f24/fs8 one of { 0, 4607182418800017408L }

f25/fs9 one of { -4616189618054758400L, 0 }

[...]

pc != mhartid

[...]

mhartid <= mip

[...]

mip <= mie

[...]

mie <= mtvec

mideleg <= medeleg

[...]

mtvec >= mcause

f0/ft0 >= f20/fs4

[...]

I’ve abridged the Daikon output file to fit on a single slide, but this covers most of the items of particular interest. We see that our zero register, x0, did in fact always contain the value 0. Additionally, note that the program counter was never equal to zero. These are both results we would expect from the RISC-V specification.

Notably, several of our floating-point registers have specific nonzero values, rather than simple inequalities like we observed in the GPRs. There are also specific values in the CSRs, which we can look up in the spec. Analyzing these specific values, as well as those in CSRs, is the next step in this research.

At this point, we’ve successfully verified the behavior of Aphrodite and its pairing with Daikon, so we can confidently claim that it does, in fact, verify properties guaranteed by the ISA specification.